Compassion Fatigue in Long-Term Care

Getting paid to do what I loved sounded great. It was anything but.

This Substack article is a supplement to a chapter I recently wrote for a new book called Relit: How to Rekindle Yourself in the Darkness of Compassion Fatigue. The book’s other 16 contributors represent a remarkable group of experts from diverse backgrounds and professions. In Relit, each of us shares hard-earned wisdom on resilience, caregiver burnout and overcoming compassion fatigue. Each chapter also provides practical, actionable advice to both professionals and family caregivers. The book will be released on November 13, 2024. You can pre-order it here.

I have a natural affinity for very old people. I think this is because I’ve always been an old soul. Contemporary culture consumes my brain, but consuming my soul are old movies, classic books, vintage clothes and any music written before 1960. As a child, I’d listen with my mom to the crackling signal of KSFO out of San Francisco (more than 200 miles away and back then dedicated to the American Popular Songbook), and she’d routinely quiz me: Who’s singing? Who wrote that song? Who’s the bandleader? No third-grader ever had a better batting average.

Decades later, I found myself at a vocational crossroads and decided to pursue recreation therapy in long-term care, working with the demographic I’d always enjoyed—especially during the 15+ years I’d spent as a volunteer leading fun activities in senior day programs and retirement homes.

It was a profession that would almost crush me.

Years would pass before I figured out that I’d fallen victim to a specific kind of burnout known as compassion fatigue. I’d heard the term but never thought it applied to me. I witnessed plenty of death and suffering in the trenches of long-term care but discovered I was pretty good at compartmentalizing. I could feel terrible in the moment but then go home, recharge and return to work the next day ready to give and listen, up for the emotional demands of the job.

It wasn’t until I understood the wider definition of compassion fatigue that I recognized its impact on me. I learned that, particularly for caregivers in a workplace setting, compassion fatigue can occur when a lack of basic resources and support systems prevents someone from fully carrying out their job. In a long-term-care home, these necessities include: sufficient staffing, functioning and accessible equipment, a suitable workspace, delineated and enforced boundaries pertaining to job duties and expectations, respect from superiors and an overall workplace ethos that prioritizes resident and staff well-being over what I call bureaucratic “box-ticking.” When substandard resources and support combine with the emotional demands routinely placed on care-giving employees, the result is chronic strain, which all too often can lead to compassion fatigue.

Needless to say, my journey to this realization was an unpleasant one.

One week after graduating from the two-year recreation-therapy program at Toronto’s George Brown College, I landed my first job in my new field. I would be helping launch a brand-new “memory floor” at a towering home in Toronto’s West End. The two women in charge were somewhat visionary. They pictured a small staff of two recreation therapists and one personal-support worker (PSW) overseeing a community of eight residents—all with varying degrees of dementia—from dawn to bedtime. I’d be working seven 12-hour days over a two-week period designing and executing daily activities and also participating in meals, eating side-by-side with the residents in the floor’s small dining room. All of this sounded terrific. Short workweeks! The latitude to create original programs and develop my own person-centered care plans! Free food! What wasn’t to love?

But before I knew it, I was in over my head. The women at the top hadn’t gone beyond the general brushstrokes of how their new project would work. When I pressed them for details, one of the woman said, “We’re empowering you to make the floor what you want it to be.” I may have been new to the field, but I recognized a cop-out when I heard one and began bracing myself.

While the two women were elsewhere in the building, the other rec therapist and I (working separate shifts) scrambled to create an overall plan for the floor. I soon discovered that the PSW only worked afternoons and evenings, which meant I needed to rely on staff from other floors to manage the residents’ personal care in the mornings. But these PSWs were often too busy with their own workloads to be of reliable help. This meant I became responsible for waking the residents up and helping some of them get ready for the day. Breakfast, lunch and dinner arrived like clockwork from the kitchen downstairs, but it was up to me to set the table, serve the food and then clean everything up. It took only one shift for me to appreciate, deeply, our floor’s double-load industrial dishwasher.

All at once, my days were filled with helping residents get dressed, scraping out dirty casserole dishes and burning my fingertips putting away plates and silverware still piping hot from the dishwasher. In between, I managed to lead exercise programs, reading circles and guitar singalongs, but unexpected tasks kept inserting themselves. When no one showed up to take a woman to her doctor’s appointment up the street, I was forced to trundle her wheelchair along the uneven sidewalk and even liaison with her doctor. When someone needed a shower (and a PSW from another floor was naturally unavailable), one of the bosses materialized and asked if I was a team player or not.

Incredibly, I was getting only a single half-hour break for a 12-hour shift, but I felt too new to question it. I invariably spent those precious 30 minutes on a curb in front of a nearby church, literally catching my breath. By the end of even a three-day week, I was too exhausted to do much of anything for at least two days—and lord help the poor husband who asked me to unload the dishwasher.

Two months into the job, when the afternoon PSW turned against me, criticizing my work and shaming me for avoiding the heavy desserts that always accompanied the evening meal, the shifts became emotionally as well as physically untenable. Three months into that job from hell, I quit.

The next gig was more of a slow burn, but my story there also had an unhappy ending thanks to crappy management. The home was on the small side, housing roughly 110 residents, and the building itself was as battle-tested as any of them. It had a single creaky elevator, an ant infestation and furniture that was falling apart. (On my second day, I moved a chair, and one of its wooden arms just snapped off in my hand.) For a while, a leak-catching bucket was a fixture in the dining room. And to my eternal frustration, equipment I relied on was always malfunctioning or not working at all, namely the DVD player in each floor’s common area, the TV remote controls and the lone department boom box.

But for a while, I actually liked it there. In school, I’d always said I wanted to work somewhere that needed me, not at a “rich-person” home decked out with fresh flowers and a baby grand piano. This place had grit, with some of its members having lived on the street and others battling drug and alcohol addiction. At least one resident was a chronic hoarder and another had a predatory “boyfriend” suspected of stealing from her. He lived off-site, and we were instructed to keep him at bay, even if it meant calling the police (which I had to do once). Punctuating the days was the regular howl of a man on the third floor, a mournful sound that would travel down the elevator shaft throughout the building, reminding us all that we weren’t in Kansas anymore.

The cramped recreation office was located directly across from the elevator, which meant a steady parade of residents. Some just wanted to talk, others had urgent needs, and staffing limitations meant it was the rec staff’s job to field everything. The challenges were endless. Residents needed help with their cable boxes, the rec-room computer, the Coke machine, their hearing aids, their clothing, their wheelchairs, their lottery tickets. One man was forever about to lose the sole of his shoe, and another was always demanding we drop everything to order him take-out. Once again, the actual rec therapy I thought I’d be doing became secondary to simply helping people with the nuts and bolts of daily life.

But I liked both the department manager and my fellow rec therapist, and for a while, the three of us made a winning “dream team,” meeting each challenge head-on and still finding time to execute a bountiful array of programs—from Knitting Circle and Bible Study to Bingo, spelling bees, bake-offs, memory competitions and programs dedicated to astronomy, current events and languages. We took residents to a Jays game, the movies, museums, Wal-Mart. We invited guest speakers, such as a nutritionist and a nature photographer. We hired all manner of “acts” to perform at our holiday and birthday celebrations. In 2014, we even hosted an elaborate, week-long “Winter Olympics,” replete with a dozen games like soccer, bowling and golf. I remember surprising myself by crafting a pretty-darned-good torch out of tissue paper and the stiff core of a tin-foil roll. At the opening ceremonies, the home’s terrific executive director, always game, ceremonially entered the room carrying the paper flame, “lighting the torch” to hearty applause.

The job was exhausting and dirty, messy and thankless, but I hung on, buoyed by my own creativity and the support of my fellow staff. Even amid the chaos, I didn’t hate it there. I told myself I was doing God’s work (after all, I did have to lead Bible Study sometimes, which for this agnostic was a hoot and a half) and truly felt I was making a positive difference for our residents.

Then things went south.

One day, a new executive director replaced the old one, and she was awful. She never returned emails and was tardy with responses to urgent questions. I had no patience with her (word to the wise: beware of any nursing-home employee in heels), and it wasn’t long before I got on her bad side. One morning she actually sent me home for insubordination. (She’d interrupted a conversation, and I’d said, “I’m talking to Julie.”) I returned to discover I was on probation for being too “emotional” to be trusted around the residents. By then, both my fellow rec therapist and our department manager had quit (and in fact, the whole place was hemorrhaging staff, largely due to this woman’s arrival), and my good attitude was dissipating fast. I can still hear this director’s voice over the PA system impatiently summoning me to her office, where I knew I was about to be chewed out for something. Then came the day she asked me to create a detailed plan for managing my workplace stress. I spontaneously stood up and told her that wouldn’t be necessary because I was tendering my resignation. I’d lasted there a year and a half.

My third and final job as a recreation therapist should have been dandy. First of all, it was part-time, just two days a week leading an exercise group on each of the home’s three floors. Easy-peasy. (Of course, it meant I needed a second job to make up for the lost salary, but a three-day-a-week office job miraculously materialized.) Also, the recreation manager was a friend of mine, an absolutely dynamic and fantastic person I’d met on my very first student placement nearly four years earlier. She exemplified everything I thought a recreation manager should be: organized, creative, flexible, encouraging and protective. She’d kept her rec team in place for an unheard-of 20 years, and getting a spot on it—even part-time—was a rare opportunity and a dream come true. And who knew? Maybe with my foot in the door, I’d become full-time one day.

Two years after I began that part-time job, my wonderful boss was out the door.

Looking back, I think she was just too good for that place. It’s been my experience that long-term care tends to abhor excellence and reward mediocrity, which is one reason there’s so much turn over. My boss was too kind and classy ever to tell me what happened, but I believe she, for whatever reason, felt forced out.

I stayed on, but as the months passed, I realized that my boss had been a linchpin, and with her gone, every last thing in our department fell apart.

The deterioration began quickly. Within days, middle managers co-opted our office, relegating us to a tiny desk in the main activities room, where they began having regular lunches, training seminars and meetings. A new recreation manager came and went, followed by a second one who was out the door within months—but not before firing the recreation therapist I liked the most. Members of the robust volunteer squad the former manager had developed and cultivated for decades began dropping off, as did members of the 20-year-strong recreation team, with young newbies from George Brown College eagerly filling the openings. A third manager came on-board and after firing one of the newcomers for wearing capri pants (a new one on me) left the building mid-shift and never came back. But because she was on indefinite “stress leave,” overseeing our department fell to the home’s upper management.

Without a buffer between our team and executive staff, there was no one to advocate for us, or to nix all the unreasonable demands that soon began piling up.

Full-time staff had normally been required to execute three daily programs and in between attend to our documentation (care plans, assessments, program evaluations and so on), plan our activities and work on department business like the monthly newsletter and calendar. But suddenly, we were also required to spend an hour feeding higher-needs residents at meals and also to assist maintenance by watering all the home’s outdoor foliage. The latter was a ridiculously time-consuming and labor-intensive task made more difficult by the fact that we were in the throes of a very hot July. Also, the plants lining the side of the building were positioned so far from the reach of the hose that watering them meant filling a bucket at a spigot and hauling it over to each plant for dousing, returning to refill it more than once.

Then we were told we needed to be getting more photographs of residents participating in activities. Taking photos was a big time-waster, requiring us to sit through the painstakingly slow process of uploading them to our lumbering laptops. And because there was usually just one person leading a program, stopping to take photos was often disruptive, undermining the objectives we had sought to achieve in the first place. I frankly didn’t bother, but the new hires seemed eager-to-please, and I witnessed more than one cart-before-the-horse scenario in which getting photos actually became more important than the activity itself. I remember a “Seniors’ Fashion Show” that consisted of nothing more than decking out residents in cheap boas, plastic tiaras and silly masks and then taking their photos in front of a special “glamour” backdrop. Another time, I stood in the doorway as a new rec therapist roused a woman sleeping soundly in her bed and then started taking pictures of her as staff gathered at the foot of the flustered woman’s bed with balloons and cake, eager to celebrate her 100th birthday. These kind of “activities” made me feel ashamed of my profession.

Soon we learned we were each being relegated to a particular floor, where we were expected to remain the entire day (freeing up the precious real estate of the main activities room). This presented all kinds of problems. For one thing, we had to haul a day’s worth of supplies up two or three flights of stairs (because we weren’t allowed to take the elevator unless we were portering residents) to the designated floor at the start of each day. And for another, we had no real place to park ourselves when we needed to regroup or work on our laptops. The floors’ common areas were packed with residents watching TV or seated around a dozen or so small dining tables, and space was always at a premium. I remember doing my work on a grimy dining chair, balancing my laptop on the window-sill.

Shortly thereafter, we were presented with a new department schedule that was laughable in its impracticality and which I refused to follow. It ramped up the number of activities on each floor to three in the morning and two in the afternoon, an absurd number made more so by the fact that each one was to be only 30 minutes with no time allotted for prep. Close to an hour was to be spent feeding, and everything else—program evaluations and prep, care plans, assessments, the newsletter and calendar, watering the plants, uploading photos, and so on—was to be squeezed in during a 15-minute period on the floors and (wait for it) the final half hour of the day.

And then the pandemic hit.

I lasted from March to October, grateful for the extra evening shifts I snagged screening deliveries and taking the temperatures of incoming staff. We did our best to carry on safely, leading the usual programs masked up and trying to stay at a safe distance from residents. But as the weeks and then months dragged on, I began to feel the diminishment of my ability to compartmentalize. I was surrounded by residents who were stuck not only in a single building but sometimes literally in one single spot. I remember in particular a line of wheelchairs in a fluorescently lit hallway on the third floor. These residents were positioned in these exact spots, every hour, every day, for months and months. Every meal, every cup of coffee or glass of juice was consumed in that dismal hallway. They had no TV and were moved only for personal care and sleep. We got them a radio and visited as often as possible with music, videos and games and to facilitate laptop Zoom visits with family, but for many if not most of these residents, such interventions weren’t enough to stave off decline.

Many, many elders declined in this fashion thanks to the pandemic.

As summer 2020 gave way to fall, I was asked more than once to enter a private room and interact with a resident who’d tested positive for COVID. It was the kind of request that made me uncomfortable and represented my personal “line.” Under those conditions, it seemed debatable whether bedside rec therapy was helpful or essential enough to justify the risk I’d be taking. As long as there were other residents in need—healthy residents with whom I could safely interact—I just didn’t see the point.

But there was no one to advocate for me. By that time, it was obvious that management and I had different objectives. Mine was simply to do my job and nurture positive changes in the well-being of our residents. Management’s goal—at least to me—was to save money by milking staff resources to the hilt and make the home look as good as possible on paper to attract more families and secure province funding.

And then the home experienced the largest COVID outbreak in all of Ontario. That was the day I decided enough was enough. As a part-time employee, I wasn’t earning enough money to compensate for the strain I was experiencing. I felt guilty about quitting but found solace in the fact that I was no longer putting my husband’s health at risk.

I’d been offered full-time hours at my office job and took them.

The seven years I spent as a recreation therapist for seniors are now in my rear-view mirror, and unless I get desperate, I never want to work in long-term care again. It wasn’t that I didn’t enjoy the work I was trained to do. For the most part, I loved the residents and the creative challenge of designing person-centered care plans, interventions and activities aimed at improving individual well-being. The problems always stemmed from the short-sightedness and inflexibility of management, which crushed my enthusiasm and stymied my ability to do my job. This combined with the structural shortcomings of many senior-care facilities—the slow elevators, the broken equipment, the ancient computers, the lack of space—made the weight of the job’s integral emotional burdens all the harder to bear.

I plan to return to volunteering one day—but even though I continue to enjoy the company of older people, it probably won’t be at a nursing home.

***********************************************************************

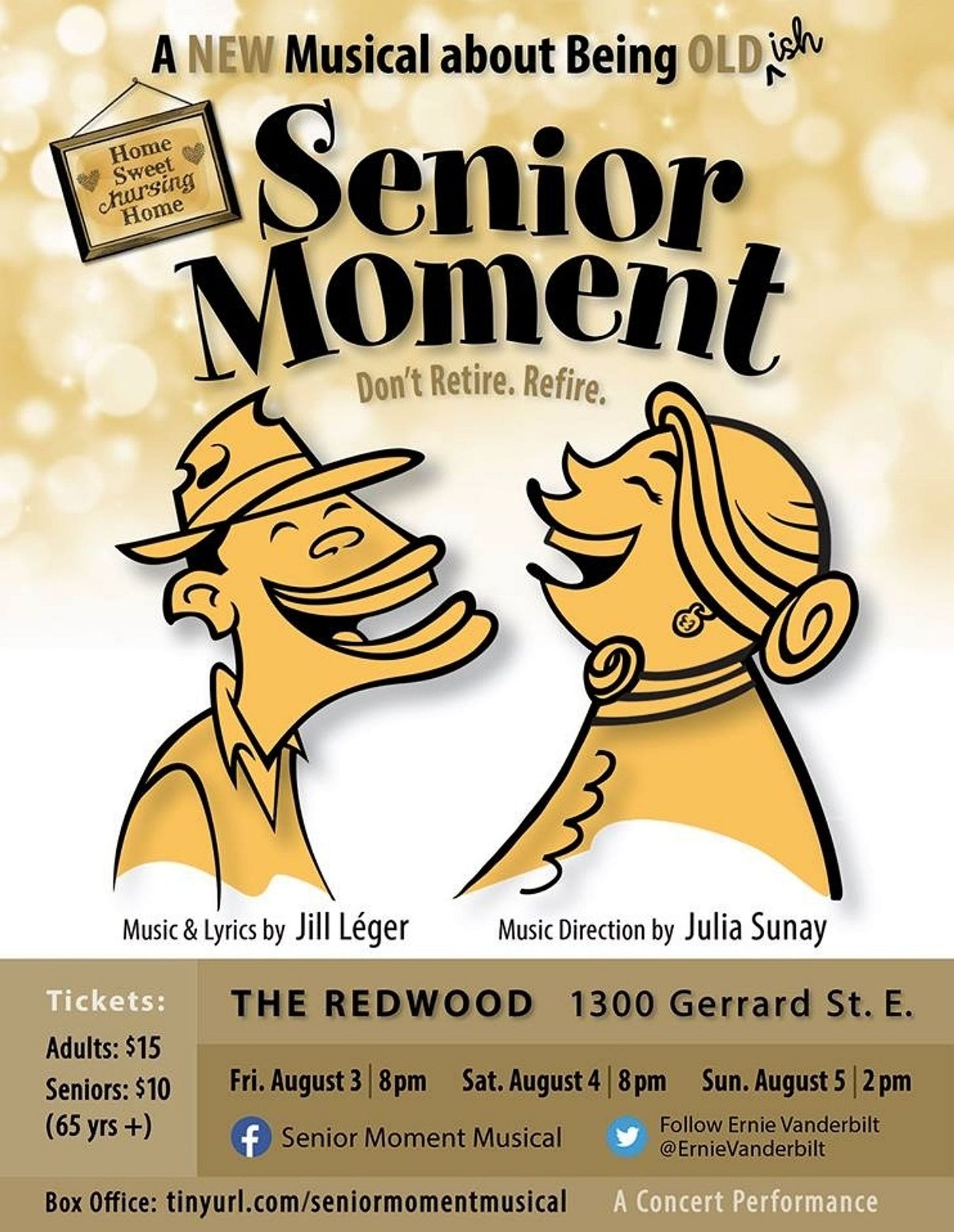

POSTSCRIPT: One day, on the floor of a packed van taking residents to Wal-Mart, I began writing a musical. It was about a group of seniors at a run-down nursing home who join forces with a recreation therapist to save their home from demolition. I got the show on its feet the summer of 2018—home-made lemonade from a whole lot of lemons.

Oh the memories that this brings. I recall the 'forced march' from eagerness to embrace the challenge, enrich the lives of residents and make a real difference to having it all taken by misguided, often abusive management. You did right by stepping away though I know it broke your heart,

This made me LOL: "beware of any nursing-home employee in high heels"

I love performing at seniors' residences, but am only there long enough to set up, perform for an hour, and then chat with residents for maybe twenty minutes' afterward. I don't think I'd be cut out for a longer stay than that.

Also - this article explains the rapid turnover in staff. On multiple occasions I've been booked by a rec director who's no longer there by the date of the performance.